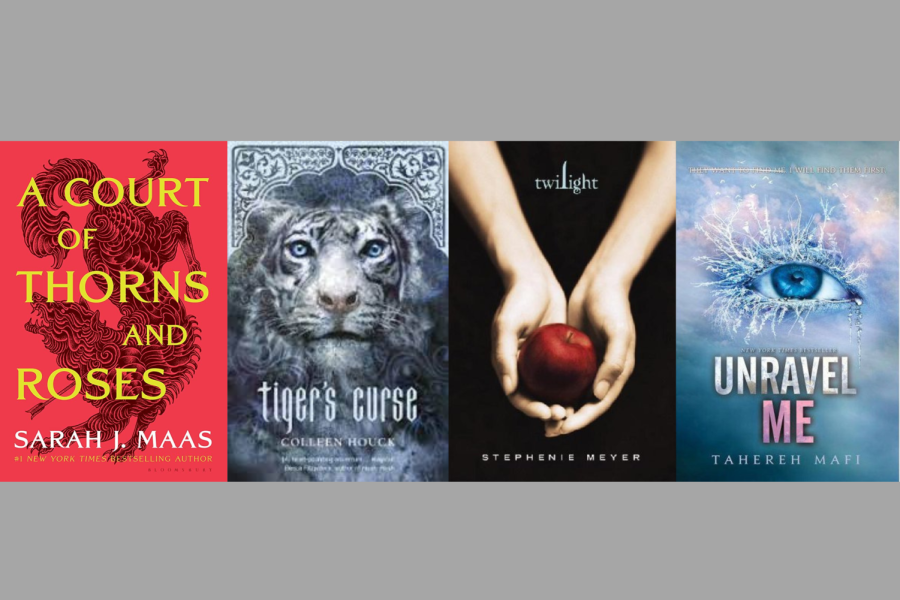

Books that have sparked controversy

Why YA Romance needs to stop romanticizing toxic relationships

The portrayals of toxic relationships can be detrimental to young readers if the topics is not handled properly.

May 17, 2023

In 2022, the highest-grossing literary genre was romance, and with the explosion of readers on TikTok with hashtags such as “BookTok”, young adult novels intended for those between the ages of 12 and 18 were sold at a greater volume and given to teenagers to read. By increasing the interest in reading among teenagers, this should be a good thing, right?

Not exactly.

Readers between the ages of 12 and 18 are a highly impressionable group. Their brains are still developing, and much of the media they consume—whether it is through books, television, movies, video games, or another form—has an impact on the way they think, behave, and perceive the world. I, myself, am a reader of both the young adult and romance genres, as well as someone who falls into this age category. The books I read had a large impact on me, particularly in middle school. From the way I dressed to the way I spoke, I found myself mimicking what I read and connecting it with my real-life experiences. I am not the only one. The rise in teenage dystopia in the early 2010s gave young people a sense of liberation and taught these audiences to stand up for themselves, the same way many other books have shaped generations to come. But these readers being so impressionable comes along with a series of negative aspects and inappropriate thought processes sparked by the books read and the content consumed.

During their middle school and early high school years, adolescents often begin to first experience romantic and sexual feelings, and in turn, readers usually begin with young adult romance. But what, exactly, bridges the difference between young adult and adult? Truthfully, it is complicated.

The traditional definition for young adult literature has to do with characters who are similar ages to the readers—12 to 18—while adult novels typically consist of characters that are, obviously, adults. The writing is often simpler in young adult books, and the themes often have to do with aspects of life the readers can relate to.

However, I’ve found many young adult books—and this number is only on the rise—contain sexual content and scenes not meant for younger audiences to consume, all without proper warnings listed anywhere. This wouldn’t be nearly as problematic if it wasn’t for the nature of these scenes wasn’t often unrepresentative of actual sex and relationships. It has become common, as well, for authors to begin their series with a tamer, young adult tone, and increase the maturity of the romantic storylines with each book. This exposes young readers to inappropriate content and can become confusing. How is one book in a series young adult whilst the next is very, very adult?

This is not a new thing, either. From the early 2000s young adult books to the present, there has been a constant romanticization of toxic relationships and abuse, without justification or a rebuttal. During the stages of the plot in which a relationship is developing, there are scenes that could be considered sexual assault and/or downright abuse, only for these instances to be forgotten about once the characters formally become a couple.

Enemies to lovers or Stockholm syndrome?

When it was first published, A Court of Thorns and Roses by Sarah J. Maas was considered a young adult novel. Feyre Archeron is nineteen years old and possesses many of the qualities that traditional young adult heroines do. For the most part, the plot feels directed toward adolescent readers. During the events of the book, we are introduced to two of Feyre’s love interests: Tamlin, the quiet (allegedly sweet) man who brings her to the Faerie world, and Rhysand, the sociopathic “bad boy” with absolutely no boundaries around Feyre. In a quote by Goodreads user “faith, trust, pixie dust,” “[Rhysand] repeatedly violates [Feyre’s] personal space and comfort, drugging her and forcing her to “dance” for him in front of a large crowd for weeks on end after stripping her all but naked. Like all Fae males, apparently, he uses brute force to get her to comply with his sexual wishes.”

Despite all of this, Rhysand still becomes the man Feyre chooses in the second book—and not to mention, Tamlin isn’t any better. He becomes possessive and controlling as well, and makes several unwanted sexual advances on Feyre throughout the story. They briefly become a couple, although he is overshadowed by Rhysand in the end.

I’m going to ask you again: What does this teach young readers about relationships? Especially young women, who may gather the idea that relationships with men are supposed to be possessive, controlling, and downright toxic. Adolescents tend to take after their role models, and since Feyre is, for parts of the story, a fairly strong female character, it could become easy to view her as a role model. Teenagers who haven’t yet experienced romance are then more likely to accept the idea that this is a standard for romance and relationships.

Toxic relationships as a lesson for readers.

Around the same time that I read A Court of Thorns and Roses and other similar books, I read the Shadow and Bone trilogy by Leigh Bardugo. Shadow and Bone has a primarily young adult plot, while still appealing to teenagers and adults alike. 17-year-old Alina Starkov lives in the fantasy nation of Ravka, a country that is divided by a massive, shadowy storm called the Fold, created centuries prior to when the story takes place. In Ravka, there are two armies—the First Army, which is similar to a regular military, and the Second Army, also dubbed the Grisha, who all bear magical powers from different orders.

Alina, a mapmaker for the First Army, discovers that she has a unique, prophesied power—the ability to summon the sun—which is the one thing that can destroy the Fold. As such, she is whisked away from the life she once knew and her childhood best friend, Mal, and introduced to the Darkling, the general of the Second Army.

While there is romantic and sexual tension between Alina and the Darkling at the beginning of the book, and readers are led to believe that the Darkling may be one of Alina’s love interests, this quickly becomes the opposite. The Darkling is the villain instead, and his actions are not justified. Halfway through the first book in the series, it is revealed that the Darkling has been lying to Alina, only using her so that he can keep her as a servant of evil instead of destroying the Fold like he previously promised. This is where Leigh Bardugo, the author, teaches the readers a lesson. Instead of promoting and justifying the Darkling’s toxicity and manipulation, Alina escapes and the Darkling into the story’s villain as opposed to a love interest.

I’ll admit that when I first read the book, I remember “shipping” the characters, asking myself, “Why does he have to be evil?” Now that I am older, I understand it much better.

This plot twist and the reaction that Alina has to it instead teaches the novel’s younger audience that men who are abusive, manipulative, and liars are not love interests and should not be pursued in relationships. Bardugo does a wonderful job at conveying the intrigue and often charming allure of the Darkling while maintaining the message that even if someone is conventionally attractive, there is more that matters than their appearance—especially how they treat you. The lesson taught can be difficult for readers to understand at first and may seem heavy for younger audiences, but it creates a healthier mindset for these readers than books like A Court of Thorns and Roses do.

Conclusion.

Although books do not have to follow one set of morals and beliefs, young adult books that romanticize and improperly portray toxic and abusive relationships do subtle harm on their impressionable audiences. Many popular young adult romance books invoke beliefs that predominantly men are allowed to treat women however they want, whether the action is sexual or physical abuse. Of course, authors shouldn’t stop writing these relationship dynamics entirely. Rather, they need to be written with more thought—a rebuttal that explains how the actions of the character are wrong—and the characters in the abusive relationship should not end up together by the closing of the book. This instills the idea in the developing brains of teen readers, especially girls, that they have control over their relationships and their partners aren’t allowed to treat them any way they want.

While books are of course allowed to have complicated morals for the sake of the story, it is important for authors to consider the ways in which they are handling sensitive topics—and furthermore, how they may impact the audiences at hand.