As ice melts and the winds warm, spring arrives, bursting sprays of flowers along our roads and tales of faeries into our storybooks. If you have ever visited a medieval church—or the spring section of Michael’s—you may have noticed the many embellishments and symbols used to represent spring, especially what seems to be the figure of a man’s face indistinguishable from nature. Appearing as a man’s head emerging from foliage or spewing leaves from its mouth and face, the Green Man is a figure entrenched in the mythological realm of Europe and springtime. Evolving from pagan mythology, medieval church decoration to the symbol of environmentalist movements, and spring today, the Green Man’s cultural history and symbolism begins centuries ago.

Lady Raglan, a 19th-century British aristocrat, provided the first speculative publication of the Green Man, dubbing him his name and publishing several books of thesis upon his symbolism and appearance on church facades. She proposed the idea that the Green Man represented pagan mythological figures and that his essence is personified through icons. In Wicca, the Green Man is a representation of the Horned God; in Celtic mythology, Cernunnos; and in Greek, Pan. These Gods are all seen as rulers or representations of nature, wilderness, sexuality, and the life cycle. There are many historical interpretations of the Green Man: some that argue against Lady Raglan’s interpretation, and others that align with it.

Figures intertwined with the Green Man have been recorded from even before the contemporary era (BCE). The “wild man,” “woodwose,” or “wodyn” was a common character in the theatrical world of Europe, always represented as a man covered in leaves, with shaggy hair and beards, leaf garlands on his head, and a club or firecrackers in hand. The earliest recorded example of this character archetype is Enkidu of the ancient Mesopotamian “Epic of Gilgamesh.” Enkidu lived in the wild alongside animals and only became civilized after falling in love. This concept may have been influenced by the description of Nebuchadnezzar II in the “Book of Daniel” —who was humbled for his boastfulness by growing hair on his body and living like a beast—and Saint John Chrysostom, whose abstinence from worldly pleasures made him so feral that the hunters who captured him could not tell if he was beast or man. In the 15th-century Breton poem “An Dialog Etre Arzur Roe D’an Bretounet Ha Guynglaff,” King Arthur meets the wild man Guynglaff, who predicts events which will occur as late as the 16th century. Several other stories, such as 9th-century Irish tale “Buile Suibhne”, the 12th century origin of Merlin “Myriddin,” and 13th-century Norwegian tale “Konungs skuggsjáthe”—the King’s Mirror—all include the imagery of an all-knowing, free, and wild man.

The creation of the “wild man” figure drew from the lore of the Roman faun and deity of woods, Silvenous, and other pagan beings. In Slavic Mythology, there are many mythological forest diviy (wild people), such as the dikar, a short man with a big beard and tail; the lisovi lyudi, old men with overgrown bears that give silver to those who rub their noses; lihiy div, marsh spirits that send fever; and divnye lyudi short, beautiful humans that have a pleasant voice, live in caves in the mountains, and can predict the future. There were even ancient folk traditions surrounding capturing wild men. For example, the peasants of Grison, a settlement of Switzerland, were believed to try to capture the “wild man” by getting him drunk and tying him up in the hopes of trading his freedom for wisdom. The ancient tradition of Silenus or Faunus, which appeared in the works of Ovid, Pauasians, and Claudis Aelians and was recorded as early as 345 BC, included a similar act of shepherds capturing a forest being. The Burgundian court even celebrated a pas d’armes known as the Pas de la Dame Sauvage (“Passage of arms of the Wild Lady”) in 1470, where a knight held a series of jousts to parallel the conquest of the female counterpart to wild man to the feats a knight must do for a lady.

The wild man character, to a lesser degree, was inspired by the writings of ancient historians and distorted accounts of apes. Herodotus (c. 484 BC – c. 425 BC) was the first historian to describe ancient wild men, localizing them to western Libya, and after the conquests of Alexander the Great, India became the primary home of fantastic creatures in the Western imagination. In the Natural History, Gaius Plinius Secundus— a roman naturalist— described a race of silvestres, wild creatures in India who had humanoid bodies but a coat of fur, fangs, and no capacity to speak. Many other accounts of encounters with wild men depict indigenous tribes and even gorillas, chimpanzees, and apes. The most infamous are the Grazers, a group of of monks in Eastern Christianity that lived alone and naked.

The main characteristic of the wild man—whether imaginative or someone simply living beyond civilization—is his wildness, and civilized people regarded wild men as the antithesis of civilization. Whereas the age of the wheel came and mankind traded their primitiveness to wield the elements for their own benefit (building fires, taming plants for harvest and wood for homes) some outliers reminded, representing the harsh reality of mankind and stripping the faux veil of society. Are we really just animals trying to paint ourselves as something moral? Even thousands of years later, the Wild Man has been discussed in Freudian terms as representative of the “potentialities lurking in the heart of every individual, whether primitive or civilized, as his possible incapacity to come to terms with his socially provided world.” He is our Id, the part of our personality present from birth: the impulsive, hungry, selfish, wanting unconscious without regard for the interests of others. The wild man is a symbol of humans still tethered to nature, still beasts, and not the slightest bit above an animal as we like to elevate ourselves.

The wild man eventually morphed and extended its meaning within the figure of the Green Man As early as the 14th century, the term “green men” finally emerged as a term on the Elizabethan stage to describe actors in leafy, mossy, or grassy costumes, dressing as foresters, savage men, and natural mythological figures such as nymphs and satyrs.

Despite being believed to be a pagan symbol, the Green Man became a common decoration on medieval churches as a symbol of transition. It is suspected that the association arose from the legend “The Golden Legend” where the biblical Adam appears as a Green Man himself, in demise by the hands of nature and time. His son, Seth, places three kernels beneath his tongue, kernels from the Tree of Life. From the body of Adam and kernels thus springs the trees that yielded the lumber of the True Cross. It seems to symbolize paganism’s transformation under the True Cross and within it, lies the idea of cyclical time and renewal. According to Christianity, Adam and Eve were exiled from the Garden of Evil for eating an apple from the Tree of Knowledge— for our attempt to rise above the natural order. It seems to be the origin of the idea of cyclical time. As time turns, the wilderness always engulfs humanity and its creations, and man always attempts to “work and keep” the garden. Old buildings get eaten by ivy, forests get cut down, over and over again. Spring and winter battle aswellI, putting nature to slumber and then awakening it, darkening the world then greening it. It is an eternal struggle where chaos is pitted against order. This explains why the Green Man appears in transitory places, external facades, and looking down upon passersby on ceilings or archways. The Green Man looks down upon men to remind us that our decision to stray from nature has made us subject to chaos.

The symbolism of the Green Man continues in the Arthurian tale of “Sir Gawain and The Green Knight,” where a struggle between time, space, death, renewal, chaos, and order is represented by the Green Knight. Gawain submits himself to the Green Knight for the purpose of the quest and follows the rules of nature, learning that it is impossible to be virtuous without being respectful to nature.

The significance of the Green Man has continued to evolve over the centuries. During the latter party of the seventeenth century England, the Green Man became a symbol for both distillers and pubs due to his antics of intoxication. According to Larwood and Hotten, authors of The History of Signboards, two signs emerged: “The Green Man and Still” and “The Green Man.”

Toward the 20th century, the Green Man became a figure of nature in literature and the arts, even leading to political movements. For example, J.R.R. Tolkien, author of The Lord of the Rings (1954-1955) introduced the species of Ents, humanoid trees that look like giant Green Men and act as defenders of the environment and trees. Dr.Seuss’s The Lorax and the many retellings of Robin Hood contain the same emblem of a green-wearing or consumed-by-nature figure that is a defender of the natural world. In the 1980s—partially because of this symbolism—the Green Man reemerged as a symbol of the environmentalist movement, personifying nature and the need for humanity to remake its relationship with it.

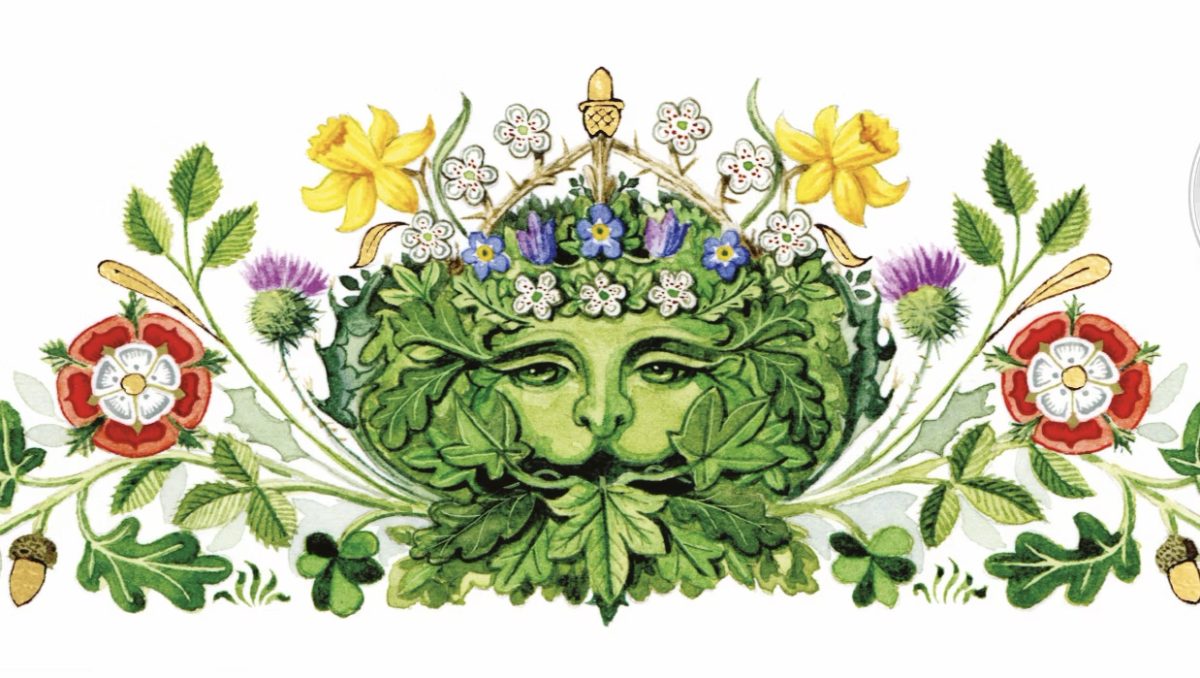

In 2023, the Green Man appeared on the invitation card of King Charles’ coronation, designed by Andrew Jamieson. According to the official royal website: “Central to the design is the motif of the Green Man, an ancient figure from British folklore, symbolic of spring and rebirth, to celebrate the new reign. The shape of the Green Man, crowned in natural foliage, is formed of leaves of oak, ivy, and hawthorn, and the emblematic flowers of the United Kingdom.” The presence of the Green Man alludes to King Charles’s identity as a nature worshiper and his political position in the environmentalist movement.

Today, the Green Man, despite not being affiliated to a certain religion and with a dubious still-debatable origin, is a prominent figure in folk revival, renaissance faire, and faerie festival movements, with many attendants of fairs and festivals painting themselves green and brandishing capes of leaves.

As humans, we cannot ignore our ties to nature. Historically, wild men and the Green Man have been viewed as something barbaric, but as a society, we are in a cycle of repairing and thinning our relationship with nature and ourselves. Historian Ronald Hutton says, “the very lack of a single definitive meaning for the Green Man image has allowed it to adopt new meanings in the modern world.” In the future as society advances and we enter an even more technological age, the Green Man may continue to develop and evolve as a figure to tether us back to the earth.

The next time you see an emblem representing nature or if you ever stumble upon the face of the Green Man, remember that we are not so separated from the natural world and our nature. We shouldn’t be.