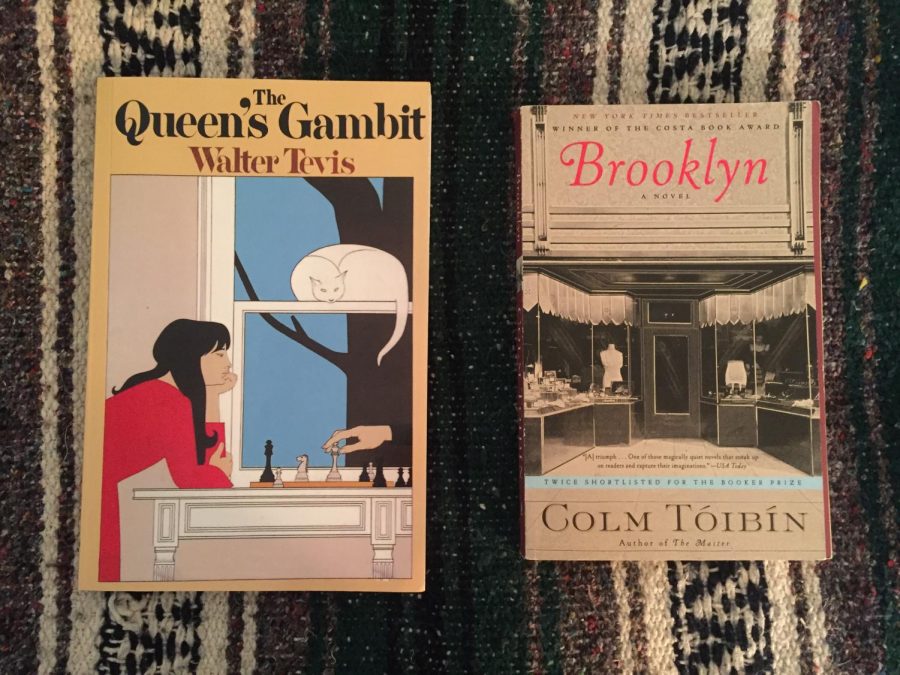

To the left: a misguided attempt, to the right: a masterpiece.

Men writing women

A case study of two novels where men write from the perspective of a woman

January 26, 2021

This article contains minor spoilers for “The Queen’s Gambit” by Walter Tevis and “Brooklyn” by Colm Tóibín.

“The Queen’s Gambit” was a phenomenal limited series that still sits with me to this day, many months after having finished it. I always try to glean something from the shows that I love– I’ll listen to the music featured, read any of the books mentioned throughout the series, and, in the case with “The Queen’s Gambit,” I’ll even teach myself chess.

However, since most– if not all– of the novels mentioned in that show were about chess played at a level I cannot yet comprehend, I didn’t follow up my viewing of the show with novels mentioned throughout the series. Instead, I read the book which served as the skeleton for the show’s screenplay: the aptly named “The Queen’s Gambit” by Walter Tevis.

“The Queen’s Gambit” (novel) fails perfectly; in that, it is a perfect representation of the pitfalls that often– but certainly not always– find male authors when they write from a woman’s perspective. Inversely, the novel “Brooklyn” by Colm Tóibín features a male author writing a female protagonist in such a convincing and raw manner that displays such a depth of understanding of the female experience that it emulates of the writings of Jane Austen.

When considering the portrayal of a woman in a novel, it is important to address some key areas: confidence, self-perception, periods, and emotional depth.

Confidence and its incessant fluctuations are a significant part of being a woman. Tevis’ depiction of Beth left me to believe that he thought that women could only express their confidence through their self-perception of their own attractiveness. Ugly? Not confident. Pretty? Confident. Simple as that, right?

As I began the book, I made a bet with myself: as Beth improved as a chess player, she wasn’t going to view herself as the ugly duckling she always saw herself, and eventually, she would sport conventionally attractive physical features. And I was right. This differs significantly from having confidence in one’s body– she grew to be objectively stunning; she did not learn to love the “ugly” body in which she was born.

In my opinion, Beth developed conventionally attractive features because Tevis thought he was creating a more clean-cut “finding confidence in oneself” narrative with this easy-to-understand physical manifestation of her beauty. However, it is important to note that a woman can grow her confidence for reasons independent from her outward beauty.

By giving Beth conventionally attractive features, Tevis sidestepped a potentially more impactful narrative where she could have accepted her body as is. So many women in the world grow up thinking they’re ugly and struggle to view themselves as beautiful throughout their lives. Tevis was almost there– he almost understood that personal journey– but he missed the mark in one significant way when he gave Beth conventionally attractive features, which, when executed in the manner he chose, weakens the “finding confidence in oneself” narrative.

Tóibín sometimes falls into a similar narrative structure, but with a few important caveats. While Eilis, the female protagonist in “Brooklyn,” does feel more confident in herself when she buys herself nicer clothes and wears some makeup, she doesn’t experience some fairy-tale-esque boom in good looks. In fact, she is described as wholly “plain” in her physical features.

Additionally, Eilis’s self-perception of her looks are not her only measure of confidence. Instead, Tevis describes Eilis’s confidence smartly through her interactions with her roommates in her boarding house, how she handles the students in her otherwise all-male bookkeeping class, and her participation in the dances thrown by her parish.

While my confidence personally swells in a form-fitting dress and a little mascara, the purely physical representation of a woman’s confidence which Tevis employs is a weak attempt to understand a woman’s internal monologue, and the more dynamic approach taken by Tóibín achieves a stunning level of realism with which I am confident that most women identify.

There is also the issue of periods. Tóibín details Eilis’s period in a clinical, realistic sense– the protagonist is not thrown off by this normal function of her body, and she continues with her day as normal. With Beth, Tevis details the first instance she ever gets her period, which, as a memorable moment for many young women in the world, is certainly noteworthy. However, due to the certain sequence of events in which it takes place, it seems to be implied that arousal acts as the catalyst for the onset of Beth’s menstrual cycle. Aside from the biology of this being simply untrue, the instance is heavily dramatized, becoming almost comical in its timing. Real periods don’t often act as the punchline to a joke.

Tóibín treats menstruation with realism and sense, but Tevis’ depiction of the event acts more like a cheap ploy to end a conversation and change the scene. Beth does not hesitate for one moment, even though it is relayed that Beth had no idea what was happening. To get one’s period when one doesn’t even know what their period is a terrifying and confusing experience. However, this apparently isn’t true for Beth, who must have known that her period was simply a plot device.

Additionally, exploring a woman’s emotional depth is another significant factor to consider when men write women. Tevis was unable to get emotionally close to his protagonist in a way I think Tóibín does. Tóibín’s Eilis is written with the maturity and understanding of one of Austen’s female protagonists. She rationalizes her thoughts, relates to the men and women around her, and succumbs to outbursts in a way in which I completely identify. Tóibín’s depiction is sound, well-rounded, and well-thought-out.

Beth’s only emotions seem to arise when she speaks about chess– consequently, the only thing that Beth and Tevis, a “class C” chess player, have in common. Tevis did not reach far beyond his own interests in his attempt to develop an emotionally-significant protagonist; he inserted his own emotions where he could, which was in chess. He did not give Beth any emotional depth independent from himself. All we know about her, really, is that she is good at chess, she is an alcoholic, and she doesn’t like to lose– and we only know that last part because she told us so at least a dozen times throughout the novel in no uncertain terms. In short, Tevis’ Beth is as emotional as a brick.

However, even if she is a brick, this emotionless protagonist serves an important, albeit lazy, Tevis function. “‘The Queen’s Gambit’ derives from an obsession similar to that which produced The Hustler [one of Tevis’ multiple famous screenplays], but deeper and older,” states the author’s blurb on the inside cover of the novel. Tevis was obsessed with the idea of a woman rising through professional chess ranks and becoming the youngest World Champion in history. It had never been done by the time of this novel’s publication in 1983, which intrigued Tevis.

Herein lies Tevis’ biggest blunder: Beth was never written to be an emotionally-significant, complex human, independent from the man who created her; she was always a plot device for Tevis to act out one of the chess world’s biggest hypotheticals.

Tevis doesn’t achieve a convincing portrayal of a woman primarily because it seems that his goal in this novel was to explore one of the many iterations of the statement “women can’t do this.” He wasn’t looking to step into a woman’s shoes and see the world through her eyes; he just wanted to use Beth as a vessel to tell the story and an empty vessel at that.

Inversely, Tóibín tells a story through the eyes of a female Irish immigrant, which, unlike Tevis’ uncharted territory, is a story that has been told millions of times in our nation’s history. Tóibín doesn’t rely on intriguing hypotheticals to define every aspect of his protagonist; instead, he explores her thoughts, rationalizations, emotions, contentious relationships, and much more with such careful consideration and understanding. In the opinion of this writer, it pays off. Tóibín created a real, breathing human, which is the ultimate goal when writing a novel.

Now, the question remains: what produced these differences in the portrayal of women between these two authors?

I possess the theory, untested by science, born from my personal reading experiences, that some of the straight male authors who fall victim to the plague which infect those featured on the r/menwritingwomen subreddit write their female protagonist in a sexual lens, first and foremost. I believe Beth Harmon, the protagonist of Tevis’ “The Queen’s Gambit,” is a product of such writing.

In my opinion, Tevis writes Beth in such a fashion because, as a straight man (if having been married to a woman is any indicator, which sometimes it isn’t, but it’s the best I’ve got), that is perhaps how he primarily sees women. He is perhaps tied foremost to a cis straight male understanding of women, which could paint women from a sexualized lens. I don’t mean to say that straight men can’t write women convincingly because they refuse to consider them solely in a purely human lens, detangled from the sexual, only that the men I am speaking of have never been women, themselves, and therefore may only rely on their own personal, sexually-tinted experiences of women to portray them.

This, I believe, can act as a barrier for some authors, preventing them from developing a sincere depth of emotion in their female protagonists. Men who write women poorly are perhaps clouded by those same subtle limitations posed against them when considering women in the real world.

However, this differs when considering Tóibín, author of “Brooklyn,” who is openly gay. In my opinion, Tóibín’s “Brooklyn” presents a more well-rounded and accurate portrayal of women because this primarily sexual lens in which Tevin is privy does not necessarily apply to Tóibín, therefore leaving him free to tell a less clouded, more raw story.

I believe this clouded perception of a certain people group also applies to straight women who write from a male perspective or any person who tries to write from a minority group, which they are not a part of. It is simply difficult to fully grasp a human, understand their psyche, and write them convincingly if that human is not exactly like oneself.

In conclusion, men can, of course, write women. And women can, of course, write men. Truthfully, it is not a matter of the gender with which an author identifies; it just depends on how willing you are to leave your shoes at home and step into someone else’s.